|

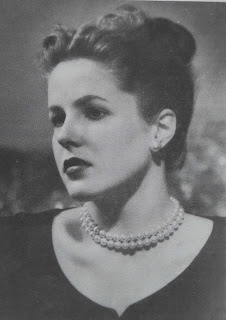

| Tally Richards, photo by Slim Arons, United Artists Pictures |

|

| In Taos, 1970, Phillip Harrington Photo |

There have been many rumors about the Tally Richards who changed her name, drank heavily, and worked as a model and chorus girl in New York. Can you set the record straight about your wild youth?

As a first question for an ARTlines interview this comes as a surprise and somewhat of a shock. When I said I have no secrets, it was said in an atmosphere of friendly exchange. I did not have the National Enquirer in mind, not even a local one, though I often deal with the baffling experiences of my life in story form or poetry; and I’m always willing to probe beneath the surface of experience in a serious way with anyone interested in doing so. Someone said, “Indifference to public opinion is an essentially aristocratic virtue.” I hope this is true, because I am indifferent to public opinion, though very sensitive to the opinions of close associates whom I respect. I would not want my reputation to reflect on them in any adverse way. This, to me, is a grave responsibility, and I’ll consider this interview an opportunity to clarify some of the misconceptions about me and my interests, both public and private.

The phrase wild youth makes me feel ancient, and simultaneously, like a child—my mother would use words such as scandal, rumors, and gossip. And I do realize that such words as New York Model /Chorus Girl produce certain assumptions. There’s a sense of shame thrown out with them for anyone who wants to catch it, as though one who would do such things is sensational, or dumb, or to use my mother’s word, common, or at the very least frivolous. In actuality, my dancing, modeling, and singing were not so different from what you did so well with the Magic Mirror Players – what Jacki McCarty, who has a flawless reputation as wife and mother, does in Taos and Santa Fe restaurants, and what young girls in Taos do in Sam’s Shop fashion shows – sing, dance, and show beautiful clothes. It’s simply a means of transporting oneself, as well as the audience, out of a mundane existence by giving visual and audible pleasure.

Change of names is another thing loaded with assumption in most people’s minds. Again, the message is that it has to do with shame, that maybe people think I’m hiding a prison record or something – God only knows what people think. The facts are that I was born Barbara Anne Stackhouse, which my modeling agent did not like, and which I did not like because people were always making jokes about my last name. The agent suggested the name Tally Richards, which he liked, and I did not like. But it was a time when women usually believed men – any man – knew more than any woman could ever know, I used the name for modeling assignments that my male agent had suggested. That led to a name change on my Social Security records, as well as other records, such as my Bloomie’s charge account. Finally it was easier to legalize the name I was using than to go back to my original name.

Wild youth? Tormented youth would be a better description. Even in my most intoxicated moments, people said I was a lady! I would give anything to be wicked and shameless and unrestrained. I went to a psychiatrist to see what he could do to help, but he said I would never be an extrovert. He said I might become a warm and charming introvert. It seems as though my twenties were spent lugging around a heavy photo book – uptown, downtown, across town – and it would always be winter, and cold, and windy. And I would always hope I wouldn’t get a job because I hate floodlights and spotlights. I felt all I could do was look pretty while waiting for Mr. Wonderful, who my mother kept assuring me was in the offing. It never even occurred to me to do anything but mark time until Mr. Wonderful came and gave me lots of children.

What I really loved to do then was to sing, and I studied with Luther Henderson, who taught Eartha Kitt and Tony Bennett and the girl who sang for Rita Hayworth in “Gilda.” Luther didn’t want me as a student because I was so inhibited, but his partner, Richard, said I had a beautiful voice and insisted I study with them. So for Richard’s sake I got a job singing in an East Side supper club. And Luther couldn’t believe that I could get a job singing when the girl who sung for Rita Hayworth couldn’t. So he came to hear me and brought a fat lady who was Bloody Mary in South Pacific. And then he couldn’t believe how great I was singing in this supper club. He didn’t know I had drunk two martinis. I had discovered that two martinis or Scotch, wine, and brandy at dinner made me feel part Latin. And I kept drinking and singing because of Richard. He believed in me. But I soon realized that martinis and Scotch were getting to be a problem, and I went to an AA meeting intending to just cut down a bit, but to my surprise and everybody else’s, I’ve never had a drink since then and only sing now in the shower.

After the AA meeting I felt part Japanese – as though I were padding about in slippers, arms folded, or, perhaps, like the Chinese, pleasant and quiet but inscrutable. It was about then that I started asking a wise friend of mine named Joseph, “What will I do when I’m old?” And each time he would say, “What everybody else does.” Not wanting to get married, I took a secretarial course. And now here I am in Taos. And no matter what I do in the future, I suppose people will be far more interested in my short stint as a Copa Girl or when I drank Scotch, wine, and brandy with dinner.

Describe the early years in Taos and the sequence of events that led you to the artists currently exhibiting in your gallery.

I came out in 1969 and was unable to find a job here. Several artists I met urged me to open a gallery for contemporary art. There was none here because there was no market for contemporary art in Taos. Having once won $102 on a $2 place parlay and with little to lose – I think I had about $500 when I arrived, of which $200 was spent on stationery, painting the walls white, and a few art books to sell – I opened the gallery, leasing the patio for what I believe was Taos’s first outdoor restaurant. Every month for nine years I was sure I would go out of business. I was never even one month ahead on expenses. Quite often the financial pressure made me wish I would go out of business, but at the last desperate moment a sale would come through, or I would be able to borrow more money.

To make matters worse, I opened a second gallery at One Ledoux and, with the first gallery at Two Ledoux, and 23 artists, it was very confusing and financially the worst year I ever had. I feel much happier now giving more space and attention to six artists, rather than feeling crowded for space and pulled apart. I was able to survive because I did everything myself – most things very badly, such as ad layouts and painting gallery walls and sculpture stands. I knew so little about what I was doing that a lot of people in those days would ask me if they could see the owner. Edmond Gaultney’s advice was to “dress better and get a beautiful tea set.” John Manchester, contradicting this, said the owner could wear anything but that what I needed was a stunning piece of jewelry to wear with jeans.

Aside from the financial pressures, it was a happy and stimulating time. Struggle usually is. It was like being very young again but with less vulnerability. The artists I’m showing now came in various ways – each an interesting story which I’m saving for a book.

Your gallery is viewed by some people as a shrine to snobbery in art. They declare that you never really take a chance on an unknown artist, or innovative art. Other people maintain that the gallery is an indispensable arbiter of quality. How do you feel about the gallery?

What arouses rage in me – besides prejudice, assumptions, and parrots – is when someone tells me that I never show young, unknown artists. As to innovation, I don’t think you’ll find a more innovative artist anywhere than Larry Bell. I have never looked at an artist’s credentials before deciding to show his work. I have looked at the work and have been sensitive to or aware of my feeling response to it. I have also never “cased” other galleries or gone after the painters who are selling well, as many gallery owners in New Mexico do. None of the gallery artists I am now showing had gallery representation in the Southwest until they showed with me. All of the artists I show now have several galleries in the Southwest.

Eleven years ago, when I started showing Fritz Scholder’s work, it had been seen in museums in the Southwest, but it had not been seen in New Mexico galleries – primarily because his paintings of Indians were too controversial. As soon as his paintings began to sell, however, every gallery in New Mexico was willing to show them. Eleven years ago Fritz was 32.

Five years ago, when Larry Bell and Ken Price began showing here, very few people in New Mexico knew their names or had seen their work, despite their international reputation with museums and serious art collectors. It was two years before I sold any of Larry’s work.

Earl Linderman, a man in his 40s, head of the Art Department at Arizona State, didn’t have a gallery because none of them thought they could sell his work. I gave him a show three summers ago, and he now has three other galleries. His shows sell out and people come to them dressed as Dr. Thrill and the Snake Lady, the fantasy characters he paints.

Brian Quinn is a young sculptor I’ve shown for several years without making a sale for him, although one of his sculptures was stolen. If in the next year or so his work begins to sell, everyone will forget the time when he was unknown and I was showing his sculptures.

I also showed Melissa Zink’s paintings before she began working with clay. She did not have a gallery at that time. I was the first to show in New Mexico the work of Lincoln Fox, when he was working with plexiglass, which was so long ago I can’t remember his original name. I’ve also shown work by Judy Rhymes, Gina Bilwin, Marcia Oliver, John Wenger, Julian Harr, and dear Tommy Hicks, who was totally unknown in New Mexico 11 years ago. Some of these people are still young, still unknown, and some have become very well-known and older. Which is not to imply that I had anything to do with the present-day situation or age of any of them

It is they who have thrown a spotlight on me. I simply provided a little space and made a few introductions for the personal satisfaction of introducing exciting new work to this area and the privilege of living with it for a short time in exchange for my time and interest. And though I agree with Will Strunk, who scorned the vague and the colorless, who said, “If you don’t know how to pronounce a word, say it loud!” I still prefer quietness, or back rows and dark corners. And I occasionally mourn the loss of privacy and long for the anonymity of Taos before moving from California.

I believe I speak for the artists I now represent, as well as for myself, in saying the financial rewards were not the prime motivation for the work that they do – in the beginning or now – any more than it is for several dedicated actresses and actors in Taos theater companies. For some, a total involvement takes place without any conscious decision being made and one is swept along in its wake. One thinks of money as a means of continuing one’s work, and if more than necessary comes along it’s an unexpected bonus and delight.

I’m in awe of the artists I represent for the risks they’ve taken, the obstacles they’ve overcome, the responsibility they’ve assumed, the criticism and misconceptions about their work that they’ve endured, the integrity they maintain, and the balance and the dignity and style with which they’ve handled success. Because of this, as I said at the start of this interview, I consider these associations a grave responsibility and quite often I feel unworthy, ill-equipped, and speechless – and here I’ve said all this. Quite often, too, I think of my gallery as some sort of miracle. I think it’s unique. Not everyone agrees – I can tell by the way the lights dim when they walk in.

Why did you choose Taos? Why have you never left?

I chose Taos because it’s different from any place I’ve ever been, yet similar to places I’ve cared for. I like variety, and it’s similar to New York in having a variety of cultures. The movement of the air at night is very similar to the air near the sea. I’ve often thought about why Taos seems to satisfy so many people who’ve lived so many other places and why those who were born here seldom leave. For me it’s somewhat like the last stop before infinity – the beautiful infinity one sees driving north from Santa Fe, at the top of the last hill before the straight-away into Taos – and sometimes it seems like heaven and earth in the very beginning. I feel at last I’m in the right place at the right time, and that I’m using all my experience and training in an integrated way. I feel the muddy season is over and spring is here with a couple of jonquils and a tulip or two. I haven’t left because I’m not quite ready for infinite beauty.

Melissa Zink said that your self-image is your main strength and main weakness. You have a conviction about your ability to do what you do and an equal conviction that you are a melancholy, shy person. How do you perceive yourself? How do you think you are perceived by the people in Taos?

I believe everyone’s main strength is also their main weakness. My main strength and weakness is my compulsive, obsessive nature. About things I like. This works well for me as an art dealer. It does not serve me well, however, with chocolates, ice cream, smoking, alcohol, or in intimate relationships.

Melissa is partly right about my convictions. I have strong convictions about the work I show, although I’ve never had strong convictions about my ability to sell the work I show, primarily because it is different, and most people are afraid or uncomfortable with anything different. And yes, I am melancholy and shy or socially awkward. Although I once thought an easy charm was what one should aspire to, I now find it hollow. Polite, unfelt phrases echo. They’re trite coverlets. I shy away from social situations where these are necessary.

I see myself as a very private-public person, a neurotic, paradoxical character who likes extremes such as New York or Taos; Larry Bell’s work, which is cool and meditative, or the work of Fritz Scholder and Earl Linderman, which is bold and colorful. Anything in between is in between.

Recently you published a book of short stories, TALLY 13. Tell me about the book and the effect your audience has had on you.

The book is a collection of perhaps the shortest short stories that have ever been written, except for John O’Hara’s. There are 13 stories on 42 pages. It took 14 years to write them. The stories can be read at fast-food counters, between futuristic transit stops, and during television commercials. Still, several friends have not had time to read them. The theme of the book is the sadness of lost intimacies in an era of great mobility, disposable products, and instant foods and gratification. Several of my friends made no comment at all, and one simply said that I failed to assert my copyrights. The most touching responses to the book were from distant, less intimate friends. One called from North Carolina, said he had just read my book and felt very close to me. And another said thank you on a picture card of Edward Hopper’s “Evening Wind,” which said better than words that I had communicated the feeling that I sometimes have. But the stories also have humor, and one friend called to let me hear her daughter’s laughter as she read one of the stories that I, too, have often laughed about. So I felt the response or lack of response revealed more about the emotional validity of my relationships than about my writing. In other words, I believe that many friendships are based on a false premise and maintained by hiding more of one’s true opinions and feelings than one reveals. And, too, writing that probes emotions deeply and honestly uncovers the unseen, unexpressed nature of the writer. And this can be a shock, a surprise, or experienced as a betrayal by someone who felt close to the writer and learns how little he knew, how distant they were.

-- Lois Gilbert, December, 1980

No comments:

Post a Comment